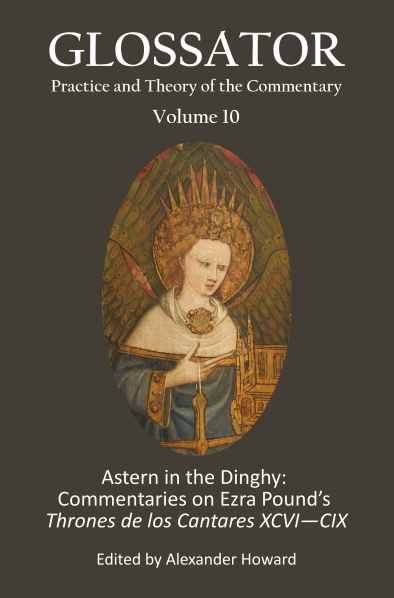

Glossator 13: In a Sea of Commentary — CFP

by nm

“Abyssus abyssum invocat” (Psalm 42)

Initial H: Fishing in the margins. Moses Striking Water from the Rock and Israelites Drawing Water in the Abbey Bible, Italian (probably Bologna), about 1250-1262. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 107.62

Premodern and modern thought on hermeneutics overflows with phrases that relate the experience of reading text and writing commentary with a submergence into the sea. Book XII of Augustine’s Confessions compares the word of scripture to a “marvelous depth” whose surface “is before us, gently leading on the little ones: and yet a wonderful deepness, O my god, a wonderful deepness” (XIV). Similarly, Saint Gregory the Great in his preface to his commentary on 1 Kings describes interpretation in oceanic terms: “we go about our labors in such enormous depths, as if we were in a huge sea” (PL 79, 21A).[1] Commentary, then, is not simply vertical or horizontal but volumetric and prismatic, buoyed by the idea that reading and commentarial practice are often discussed in terms of water: the surface becomes the depth. Just as Jacques Cousteau describes diving as “an instrument of observation,” commentary is produced in and by a condition of depth and submersion, as opposed to gazing from a surface. Water reveals and reflects; it is variable and fluid. As Gaston Bachelard writes in Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, water in relation to language is “the mistress of liquid language, of smooth flowing language, of continued and continuing language … liquidity is the very desire of language.”[2] Commentary follows this liquid logic, flowing and pooling around the text, pouring into the margins.

Contemporary formulations of interpretation and reading are also inundated with the phenomenon that configures the surface of the text as something to plunge into. Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus’s chapter, “Surface Reading,” in the 2009 issue of Representations marked a clear change in the configuration of reader and text as a relationship between surface and observer. This formulation that steers the reader to remain close to the surface is one that indicates an orientation towards the aquatic: our minds are with the sea.

Other contemporary and digital media theories underscore the substantial amount of communication that occurs undersea. Opting instead for a position of interpretive submersion, Melody Jue’s Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater takes up the element of seawater to “attend to the ocean as an environment of interpretation.”[3] While “the cloud” designates an aerial and atmospheric image to conceptions of digital media, the majority of media that rely on network transmissions are materially grounded on the seafloor. At times, the “cloud” of our world lies beneath the sea; the abyss of the ocean illustrates the substratum of communication and commentary. The infrastructure of commentary is both beneath the surface of text and beneath the sea, a dual submersion.

The inscrutable depth of a work is the object of commentary, to plumb the core of incomprehensibility that is at the bottom of the text’s abyss and bring back the strange and the beautiful to the surface.[4] Commentary is that “great periplum [that] brings in the stars to our shore,” a slow voyage that offers the recursive chance to dive into each poetic image.[5] Water and her various bodies encompass the sacred and the mundane in a variety of associations in literature, art, theology, and science. Hinting at the bleeding of boundaries between the terrestrial and the divine, the watery and abyssal o en surface in text as a lexicon for movement between two destinations.

In attending to the variety of approaches that water and its surfaces and depths have been deployed in literature and art throughout history, this issue of Glossator proposes an interdisciplinary approach to the ways that text mingles with the liquid and its entanglement with commentary. We welcome commentaries on texts connected with sea, water, abyss, etc. as well as essays exploring the nature of commentary in relation to these themes. Contributions should be 4,000 – 6,000 words in length and may focus on any historical period(s). Contributors should consult the journal’s guidelines at this link, and to look through the archive here.

Please send proposals of 300-500 words to glossator.abyss@gmail.com by December 15th, 2023

Volume Editor: Alexa Climaldi (CUNY Graduate Center)

Our timeline currently follows this trajectory:

- Proposals of 300-500 words by March 1, 2024

- First full drafts due July 1, 2024

- Final review Summer 2024

- Publication Fall 2024

[1] Henri de Lubac’s Exegese Medievale traces this sentiment with a variety of examples, particularly in chapter two, section 1: “Marvelous Depths.”

[2] Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, p.187.

[3] Jue is also considering the ocean humanities and their relationship to representations of the sea in literature and media, not just an oceanic interpretive practice.

[4] Hannah Arendt in the introduction to Illuminations: “Like a pearl diver who descends to the bottom of the sea, not to excavate the bottom and bring it to light but to pry loose the rich and the strange, the pearls and the coral in the depths, and to carry them to the surface, this thinking delves into the depth of the past – but not in order to resuscitate it the way it was and to contribute to the renewal of extinct ages”(15).

[5] Pound, The Cantos, LXXIV, p. 445. Periplum is used by Pound to describe the movement of a voyage and is derived from the Greek peri, meaning “around” and plous, meaning “voyage” or “sailing.”